The Shrinking Middle Class: By the Numbers

The Tightening Squeeze of City Living

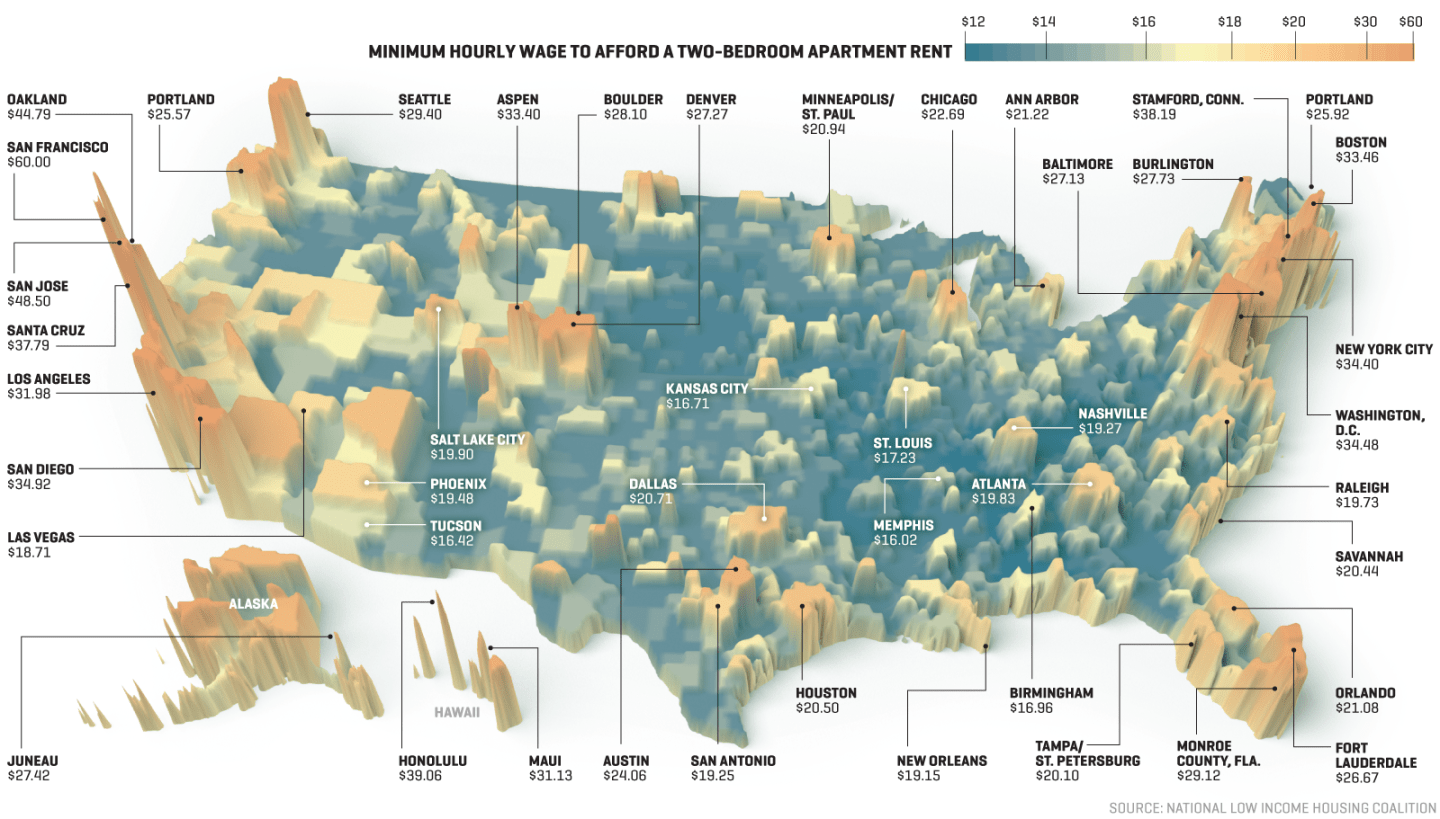

The information revolution has increased the concentration of jobs in certain U.S. cities, especially in a few hotly competitive coastal metro areas. That dynamic has driven housing costs beyond what many middle-class earners can afford, making it harder for them to save for home ownership or other financial goals. (The median U.S. hourly wage was $27.35 in November; it’s lower in most of the Midwest and South.)

Methodology info (PDF)

To The Victors Go The Spoils

Tax breaks for investors and property owners have helped concentrate wealth among the top 10%. The growing impact of higher education on earnings has had a similar effect. Since 1995, average income for graduate degree holders has risen 28%; for those with only a high-school diploma, that figure is 5%.

In Awkward Global Company

The bottom 90% of U.S. earners take home a smaller share of income than do their counterparts in most industrial economies—including in far less free societies like China’s.

Purchasing Power And Savings Wane

Incomes haven’t risen as fast as rent, medical costs, or tuition—three of the biggest burdens for U.S. households. As a result, savings rates have declined, leaving middle-class earners more vulnerable to being bankrupted by an emergency or a job loss—and less able to put away money for retirement or for future generations.

A version of this article appears in the January 2019 issue of Fortune as part of the special report, “The Shrinking Middle Class.”