How NASA's Mars Rover, and a Mohawk, Changed My Life

Curiosity touched down on Mars a decade ago, setting a new course for human exploration -- and my career.

A decade ago it was a sky crane, a be-mohawked NASA engineer named Bobak and a $2.5 billion rover called Curiosity that took my career in a new direction.

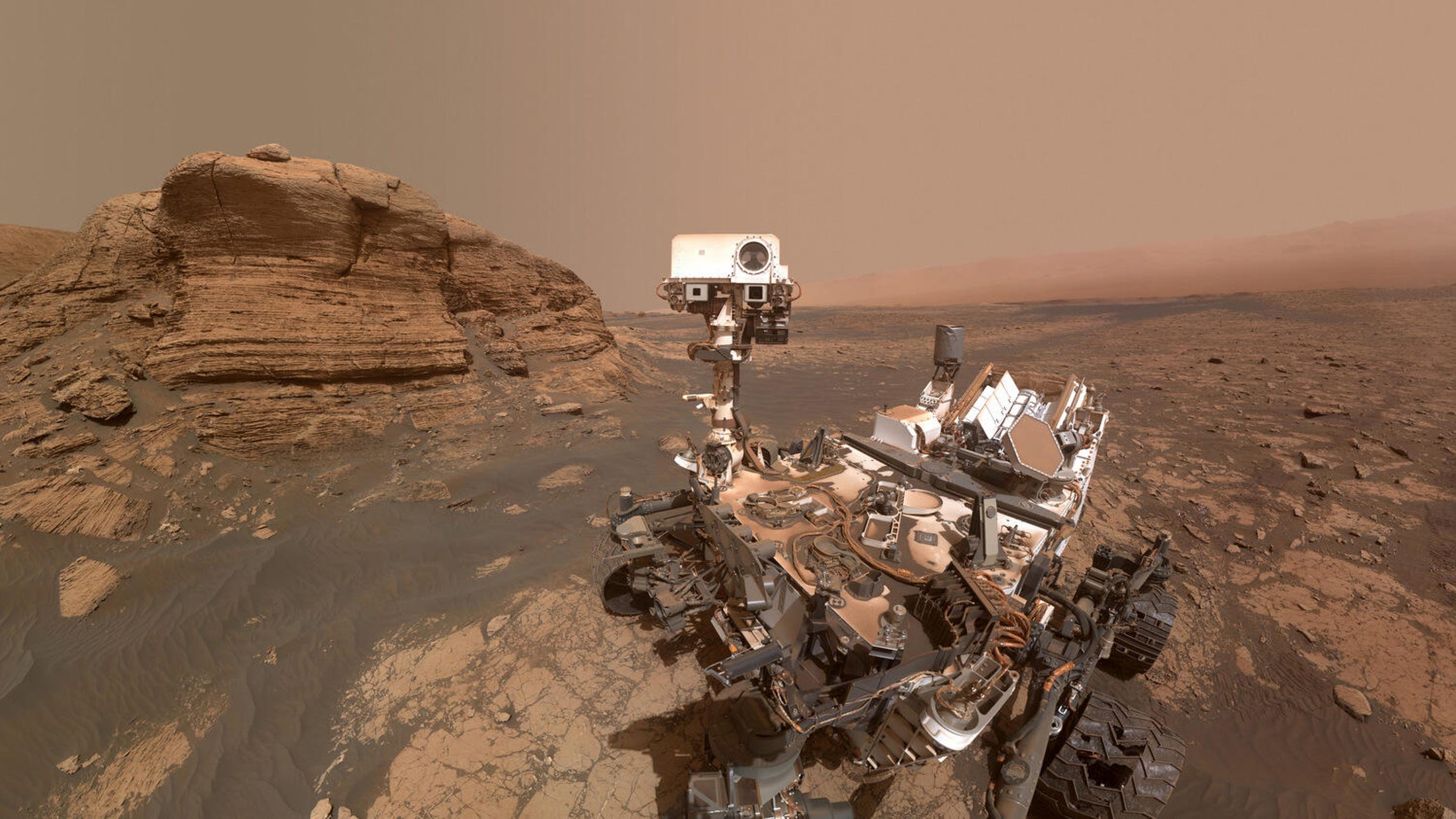

Mainly, it was the high-resolution photos that NASA's state-of-the-art rolling robot sent back from its new permanent home on Mars that got me. At the time, for the first time in human history, Earth was a world suddenly full of photographs of almost everything and everyone, thanks to smartphones. But it was the crisp photos of a completely empty world that seemed most meaningful to me, for reasons I still struggle to put into words 10 years later.

Late on a Sunday night on Aug. 5, 2012 -- the eve of my 33rd birthday -- I braced with the rest of humanity as NASA pulled off a never-before-attempted maneuver, using a system dubbed sky crane to lower its most advanced mobile Martian laboratory to the red planet's surface. Basically, a special descent system came to a hover just above the ground, lowered Curiosity on cables, detached itself and flew away to crash-land at a safe distance.

NASA called the high stakes landing "seven minutes of terror." If it didn't work perfectly, years of engineering work and billions of dollars would be wasted.

Of course, it did work, and in the process, mission control cameras caught flight director Bobak Ferdowsi at work in his trademark mohawk, and catapulted him to viral internet fame.

In a weird way, Ferdowsi -- aka "NASA Mohawk Guy" -- became the image most associated with the Curiosity landing.

Mohawk + science = awesome.

But I was awestruck by the images coming back from Mars, even before Curiosity's landing. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter returned a photo of the rover making its parachute-assisted descent through the thin Martian atmosphere, with the clear, barren landscape of another planet below as a backdrop.

Remember, this was 2012. The iPhone had been around for only five years. As a technology journalist, my days were consumed by the battle for smartphone supremacy between Apple and Android, the rise of Instagram and a now-shocking amount of excitement over something called Google Glass.

The mobile and social revolutions were quite literally eating the world, even helping to topple oppressive regimes in the Arab Spring the previous year.

And yet, such inspiring stories started to seem to me more the exception that proved the rule: Social platforms paired with ubiquitous devices boasting not one but two cameras encouraged an emerging culture of oversharing and self-obsession. I recall that around the time I started to feel this way, I hadn't expected to become such a grumpy old man in my early 30s.

Fortunately, the image of Curiosity drifting toward a completely alien and empty world, alongside images of Ferdowsi and colleagues celebrating an accomplishment over a decade in the making, was the perfect antidote for my creeping misanthropy.

The prospect of using emerging technology to push our field of view ever further out into the universe, or into the nooks and crannies of unexplored worlds, seemed infinitely more inspiring than the latest new iPhone feature.

The images that rolled in from Curiosity over the months and years that followed revealed a world that was foreign but also discordantly familiar. Mars is a dry, dead and dusty world of desolation, but it does look an awful lot like parts of the southwestern United States, which I've called home for much of my adult life. The color landscapes sent back by the rover could easily fit into a photo album of any number of hikes I've taken in parts of Utah, Arizona and New Mexico.

As Curiosity was roving these unexplored yet eerily recognizable locales, NASA's Kepler Space Telescope was expanding my mind and our understanding of the universe even further with its regular discoveries of planets beyond our solar system.

For centuries, humans could only speak of less than a dozen planets that we knew of. It wasn't until the 1990s that astronomers spotted the first exoplanet. Kepler added thousands of new worlds to our running catalog, which is surely missing billions yet to be discovered -- billions of billions, even.

It's hard to consider which smartphone app offers the perfect filter for a sunset selfie once you've begun to ponder what sunsets from other suns look like.

Without ever declaring a shift, I began writing less about tech and more about science, particularly planetary science and astronomy. And, of course, whatever Elon Musk and SpaceX and the other billionaire space bros got up to. Say what you will about them, but it's clear that Musk and Jeff Bezos both had similar epiphanies that shifted part of their focus from tech to space. I get it, and I want to see where it takes them and us.

Eight years after Curiosity survived its seven minutes of terror, it was followed by the Perseverance rover, which carried a tiny helicopter called Ingenuity. The landing in February of 2021 and Ingenuity's flights in the months that followed were a welcome distraction from the second year of a grinding pandemic.

If I'm honest, COVID-19 has made me wonder if I'm focusing too much on space. Maybe I've been a bit negligent, even decadent, in turning my gaze away from so many problems on Earth to quite literally make a career of just pondering the cosmos.

The jury is still out on that for me, but it's now 10 years after I first became captivated by a robot named Curiosity and the world briefly fell in love with an engineer named Bobak sporting a punk haircut. I think about the decade he spent with countless other engineers and scientists working toward that seven minutes of terror. That team solved the problem of how to gently place a wheeled science laboratory on another planet none of us has ever visited and never will. That's problem solving acumen on an insane level.

Curiosity inspired me to ponder the cosmos, but it inspired some more-capable specimens of our species to pursue the cosmos. I suspect that tackling challenges that are literally otherworldly in scope will actually make those more pressing challenges here at home a little less insurmountable.

So with an earnestness that I feel toward very few robots: Happy anniversary, Curiosity, and thanks.