There was once a father who had two sons. The elder was clever and sensible and knew the right thing to do in all circumstances, but the younger boy was stupid, and couldn't understand anything nor learn anything And when folk looked at him, they would say: "He's going to be a burden to his father!" If there was something that needed doing, it was the elder boy who always had to see to it. But if his father told him to fetch something late in the evening or even at night-time, and his way went past the churchyard or some other shuddery place, he would reply: "Oh no, father, I won't go that way; it makes my flesh creep!" For he was scared. Or if stories were being told round the fire at evening – the sort that make your hair stand on end – the listeners would sometimes say: "Oh, it makes my flesh creep!" The youngest son would sit in the corner and listen to what they were saying, but he couldn't grasp what it was supposed to mean: "They keep on saying: 'It makes my flesh creep! It makes my flesh creep!' My flesh doesn't creep: likely it's another of those skills I don't understand."

Now it so happened that his father once said to him: "Listen to me, you in the corner, you're getting to be a big, strong boy; you must learn some trade, so that you can earn your keep. Look at the pains your brother takes, but you're just a waste of beef and bread." "Oh, father," he answered, "I'd be glad to learn something; if I could, I'd like to learn flesh-creeping; I don't understand it at all so far." The elder boy laughed when he heard that, and thought to himself: heavens above, what an idiot my brother is; he'll be useless all his life long. As the twig is bent, so the tree grows. His father sighed and answered: "You'll learn flesh-creeping soon enough, but you won't earn a living by it."

Not long afterwards the sexton came visiting their house, and the father complained to him about his troubles, telling him how his younger son did so badly at everything, knew nothing, and learned nothing. "Think of it: when I asked him how he was going to earn a living, he actually wanted to learn flesh-creeping." "If that's all he wants," answered the sexton, "he can learn that from me. Just send him to me, and I'll soon knock the corners off him." The father was content with this, for he thought: after all, this will make the boy shape up a bit. So the sexton took him into his house, and it was his job to ring the bell. After a few days the sexton woke the boy around midnight, told him to get up, and climb the church tower and ring the bell. You shall learn what flesh-creeping is all right, he thought, and went stealthily ahead of the boy.

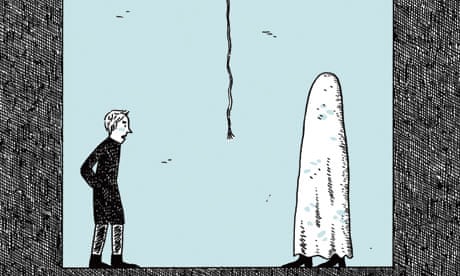

When the boy had reached the top and turned round to grasp the bell-rope, on the stairs opposite the window he saw a figure in white. "Who's there?" he called, but the figure gave no answer, and didn't move or stir. "Answer me," called the boy, "or be off with you. You've no business to be here at night." But the sexton remained motionless, so that the boy would believe it was a ghost. The boy called for a second time: "What do you want here? Say something, if you're an honest fellow, else I'll throw you downstairs." The sexton thought: he doesn't really mean it, uttered not a sound, and stood there as if he were made of stone. Then the boy shouted at him for a third time, and as that too was in vain, he took a run and kicked the ghost down the stairs, who fell 10 steps down and ended up lying in the corner. Then the boy rang the bell, went home, and without saying a word, went to bed and fell fast asleep. The sexton's wife waited a long time for her husband, but there was no sign of his return. In the end she grew fearful, and she woke the boy and asked: "Do you know where my husband is? He went up the tower ahead of you." "No," answered the boy, "but there was someone standing on the stairs opposite the window. He wouldn't answer and he wouldn't go away either, so I took him to be a villain and kicked him down stairs. If you go over, you'll see whether it was him. If so, I'm very sorry." The sexton's wife ran off and found her husband lying in a corner and moaning, with a broken leg.

She carried him down and rushed off screaming to the boy's father. "Your boy," she cried, "has brought calamity upon us; he threw my husband down stairs so that he's broken his leg. Get that good-for-nothing out of our house." The father was horrified, came running up, and gave the boy a good dressing-down. "What kind of godless tricks are these? The devil must have put the idea into your head." "Father," he answered, "just listen, I'm innocent. He was standing there in the night like someone who was up to no good. I didn't know who it was, and I told him three times that he should say something or be off." "Oh," said his father, "you bring me nothing but calamity; out of my sight; I don't want to see you again." "Yes, father, I'll be glad to. Just wait until it's day, and then I'll go out and learn flesh-creeping. And then I will have a skill that will keep me fed." "Learn what you want," said his father, "it's all the same to me. Here are 50 talers. Take them with you out into the wide world and don't tell anyone where you come from or who your father is, for I can only be ashamed of you." "Yes, father, as you wish; if you don't expect anything more than that, I can keep that in mind easily."

Now when day broke, the boy put his 50 talers in his pocket and went out on to the great highway, saying to himself all the time: "If only my flesh would creep! If only my flesh would creep!" Just then a man came by who overheard the conversation the boy was having with himself, and when they had gone a bit further, so that they could see the gallows, the man said to him: "Look, that's the tree where seven men have just married the hangman's daughter, and now they're learning to fly. Sit yourself beneath it and wait until night comes. Then you'll learn flesh-creeping all right." "If that's all it takes," answered the boy, "it's easily done; but if I can learn flesh-creeping so quickly, you shall have my 50 talers. Just come back tomorrow morning and see." Then the boy went up to the gallows, sat down beneath it, and waited until evening. And because he was cold, he lit a fire. But around midnight the wind was so chill that, in spite of his fire, he couldn't get warm. And when the wind jostled the hanged men against one another, so that they swayed to and fro, he thought: you're freezing down here with a fire; how they must be freezing and shivering up there! And because he was a kind-hearted boy, he leaned the ladder against the gallows, climbed up, unhooked them one by one, and fetched them down, all seven. Then he stoked the fire, blew on it, and sat them around it to warm themselves. But they just sat there without stirring, and the fire caught their clothes. Then he said: "Take care, else I'll hang you back up again." But the dead men didn't hear him; they sat there in silence and let their rags go on burning. Then he grew cross and said: "If you don't look out, I can't do anything for you; I don't want to burn with you," and he hung them back up in a row. Then he sat down by his fire and went to sleep. Next morning the man came up to him and wanted to have the 50 talers, saying: "Well, now do you know what flesh-creeping is?" "No," he replied, "where am I supposed to have learned it? That crew up there haven't opened their mouths, and they were so stupid that they let the few old rags they were wearing catch fire." The man saw that he wasn't going to win his 50 talers that day, so off he went, saying: "I've never seen anyone like that before."

The boy went his way too, and began to talk to himself once again: "Oh, if only my flesh would creep! Oh, if only my flesh would creep!" A carter who was striding along behind overheard him and asked: "Who are you?" "I don't know," answered the boy. "Where do you come from?" "I don't know." "Who is your father?" "I mustn't say." "What are you muttering to yourself all the time?" "Oh," answered the boy, "I wanted my flesh to creep, but nobody can teach me." "Give over your stupid chatter," said the carter. "Come with me, and I'll set about finding a place for you." The boy went with the carter, and that evening they reached an inn where they meant to stay the night. Then as they were entering the parlour he said once again, out loud: "If only my flesh would creep! If only my flesh would creep!" The innkeeper, who heard him, laughed and said: "If that's what you're after, there should be plenty of opportunity here." "Hush," said his wife, "so many have paid for their curiosity with their lives already. It would be a shame and a pity for his pretty eyes if they weren't to see the light of day again." But the boy said: "Even if it is very hard, I really do want to learn it; after all, that's why I set out." He gave the innkeeper no peace until he told him that not far away there was a haunted castle where a boy could certainly learn what flesh-creeping was. All he had to do was keep watch there for just three nights. The king had promised that whoever dared to risk it might take his daughter for his wife, and the daughter was the most beautiful maiden that the sun had ever shone upon. There were great treasures hidden in the castle too, guarded by evil spirits. The treasures would then be opened, and could make a poor man rich enough. Many had gone in, for sure, but nobody yet had come out again. Next day the boy went before the king and said: "With your permission, I would like to keep watch for three nights in the haunted castle." The king gazed at him, and because the boy was to his liking, he said: "You may ask for three things – but they must be things without life – and you may take them with you into the castle." So he answered: "Then I would ask for fire, a turner's bench, and a woodcarver's bench with a knife."

The king had these things taken to the castle for him by day. When night began to fall the boy went up and lit a bright fire for himself in one room, placed the carver's bench with the knife next to it, and sat on the turner's bench. "Oh, if only my flesh would creep!" he said. "But I won't learn it here either." Towards midnight he was about to stoke up his fire; as he was blowing on the embers, there came a sudden wail from one corner. "Miau, miau! We're freezing!" "You fools," he called, "what are you wailing for? If you're freezing, come and sit by the fire and warm yourselves." And just as he'd said this, two huge black cats came with a mighty leap and sat down on either side of him, and looked at him fiercely with their blazing eyes. After a while, when they had warmed themselves, they said: "Friend, shall we play a game of cards?" "Why not?" he answered. "But show me your paws first." Then they stretched out their claws. "Aha," he said, "what long nails you have! Wait, I must cut them first." Then he grabbed them by the collars, lifted them on to the carver's bench, and clamped their paws down tight. "I've been keeping an eye on you," he said. "I've lost my appetite for card-playing," then he killed them dead and threw them out into the moat. But when he had sent the two to their rest and was about to sit down by his fire once more, black cats and black dogs on red-hot chains came out from every corner, more and more of them, so that he couldn't get away from them any longer. They roared and screamed horribly, stamped on his fire and pulled it apart, wanting to put it out. He watched calmly for a while, but when it seemed to him to be going too far, he seized his carving knife and cried: "Away with you, you riff-raff," and struck out at them in all directions. Some of them leaped away, others he killed dead and threw out into the moat. When he came back he blew on the sparks to stoke up his fire afresh, and warmed himself.

As he was sitting there like that, he could no longer keep his eyes open, and the wish for sleep came over him. He looked round and saw a huge bed in the corner. "That suits me fine," he said, and lay down on it. But just as he was about to close his eyes the bed began to move of its own accord, and carried him all round the castle. "That's fine," he said, "only do it faster." So the bed went rolling as if it were being pulled by six horses, in and out of doorways and up and down stairs; all of a sudden, flop, flip, it turned upside down, topsy-turvy, so that it lay on top of him like a mountain. But he threw the covers and pillows into the air, clambered out and said: "Climb aboard, anyone else who wants a ride is welcome to it," lay down by his fire and slept until day. In the morning the king arrived, and when he saw him lying there on the ground, he thought the ghosts had killed him and that he was dead. "It's a pity; he was such a handsome boy." The boy heard him, sat up, and said: "It hasn't come to that yet." The king was amazed, but he was very glad, and asked how he had fared. "Pretty well," he replied. "One night has gone by, and the other two will go by as well." When he returned to the inn, the innkeeper opened his eyes wide. "I didn't think," he said, "that I'd set eyes on you alive again; have you learned what flesh-creeping is now?" "No," said the boy, "it's all been in vain. If only somebody could tell me!"

The second night he went up into the old castle again, and began his same refrain once more: "Oh, if only my flesh would creep!" As midnight approached a thudding and a banging could be heard, softly at first, but then louder and louder, then it went quiet for a moment, till at last half a man came tumbling down the chimney with a loud shout, falling right in front of him: "Hey," he cried, "you need another half still; one is not enough." Then the din started up again, roaring and howling, and the other half fell down too. "Wait a moment," said the boy, "I'll just blow the fire up for you." Once he'd done that and looked round again, the two halves had joined together and a fearsome-looking man was sitting on his seat. "That wasn't the bargain," said the boy; "that's my bench." The man made to push him off, but the boy wasn't going to put up with that, shoved him heartily away, and sat down on his own seat again. Then still more men fell down the chimney, one after another. They fetched nine dead men's shinbones and two dead men's skulls, set them up, and played a game of skittles. The boy wanted a game too, and asked: "Listen, can I join in?" "Yes, if you've got any money." "Enough," he answered, "but your bowls aren't quite round." So he took the skulls, put them on the turner's lathe, and turned them until they were round. "There, now they'll skim more sweetly," he said. "Hey, now we'll have fun!" He joined in the game and lost some of his money, but when 12 o'clock struck everything vanished before his eyes. He lay down and went peacefully to sleep. Next morning the king arrived and wanted to find out what had happened. "How did you fare this time?" he asked. "I played skittles," the boy replied, "and I lost a few farthings." "Didn't your flesh creep, then?" "What's the use?" he said, "I just had fun. If I only knew what flesh-creeping was!"

On the third night he sat down on his bench once again and said, quite out of humour: "If only my flesh would creep!" As it was growing late there came six tall men bearing a coffin on a bier. Then he said: "Oh, that's my close cousin, for sure, who died only a few days ago." He beckoned with his finger, calling: "Come here, cousin, come." They placed the coffin on the ground, but he went up to it and took off the lid; a dead man was lying in it. He felt his face, but it was as cold as ice. "Just a moment," he said, "I'll warm you up a bit," went to the fire, warmed his hand, and laid it against his face. But the dead man still remained cold. Then he lifted him out of the coffin, sat down by the fire, and took him on his lap, rubbing his arms to set his blood in motion again. When even that was no help, it occurred to him that when two lie together in bed they warm each other, so he took him to bed, covered him up, and lay down at his side. After a while the dead man warmed up and began to stir. Then the boy said: "You see, cousin, haven't I warmed you up!" But the dead man rose and cried: "Now I shall throttle you!' "What!" he said, "is that all the thanks I get? Back in your coffin with you this moment," lifted him up, threw him inside, and shut the lid. Then the six men came and bore him away again. "My flesh just won't creep," he said. "I'm not going to learn how to do it here if I stay all my life."

Then a man entered who was taller than all the others, and who looked terrifying; but he was old and had a long white beard. "Oh, you miserable rogue," he cried, "you shall learn very soon what flesh-creeping is, for you are to die." "Not so fast," replied the boy, "for if I'm to die, then I must be in at the death too." "I'll come and get you," said the fiend. "Gently, gently, don't talk so big; I'm as strong as you are, stronger, I expect." "We'll see about that," said the old man. "If you are stronger than I am, I will let you go; come, let's see." Then he led him down dark passages to a smithy, took an axe, and with a single blow struck one anvil into the ground. "I can do better," said the boy, and went up to the other anvil; the old man stood close by him, wanting to watch, and his white beard hung down. Then the boy seized the axe, split the anvil with one stroke, and trapped the old man's beard in the cleft as he did so. "Now I've got you," said the boy, "now you're the one to die." Then he seized an iron rod and went for the old man, beating him until he whimpered and begged him to stop, saying he would give him great riches. The boy drew out the axe and let him go. The old man led him back into the castle, and in a cellar showed him three chests full of gold. "Of these," he said, "one is for the poor, the other is for the king, and the third is yours." Meanwhile it struck 12, and the spirit vanished, so that the boy was standing in the dark. "I'll be able to find my way out, though," he said. He groped about, found his way into the room, and there he fell asleep by his fire. Next morning the king arrived and said: "Now have you learned what flesh-creeping is?" "No," he answered, "but what is it? My dead cousin was here, and a man in a beard turned up, who showed me a lot of money down below, but as for flesh-creeping, nobody told me what it is." Then the king said: "You have released the castle, and you shall marry my daughter." "That's all fine and good," he replied, "but I still don't know what flesh-creeping is."

Then the gold was brought up from the cellar and the wedding was celebrated, but the young king, dearly as he loved his wife, and happy as he was, still kept on saying: "If only my flesh would creep! If only my flesh would creep!" At last his young wife was vexed at this. Her chambermaid said: "I'll come to the rescue; he shall learn flesh-creeping all right." She went out to the brook that flowed through the garden and fetched a whole bucketful of little fishes. At night, when the young king was asleep, his wife was to pull off the coverlet and pour the bucket of cold water with the gudgeons over him, so that the little fish all wriggled on top of him. Then he woke up and cried: "Oh, my flesh is creeping! My flesh is creeping, wife dear! Yes, now I do know what flesh-creeping is."